As I stated at the onset of my last paper, “Proximity Alert,” it can seem like the cards are always stacked against the artist who is committed to communicating something in a very “realistic” fashion. Aside from the numerous factors and considerations that are somewhat obvious to the novice, less evident traps and procedural pitfalls await those that survive the early snares–daring to push onward.

While my last paper focused on considerations of proximity in regards to perceived shape, size, curvature, etc., my aim here is to examine the impact of proximity on perceived values and value relationships.

I have often heard art teachers tell students to step away from their drawings/paintings during their process so that they may better see what they are doing. Now I am not sure that “better” is the right word to use here, but stepping back to look at your work can indeed provide some incredibly helpful information for the observational realist. Let’s look at how:

First, it is important to understand that our vision is dependent on contextual relationships. The environment that surrounds a particular stimuli directly influences our perception of it. With that understood, you should be aware that our foveal vision (center of vision/region of the retina with the highest acuity) sees only the central two degrees of the visual field. The size of this region of the visual field is approximately the area of your thumbnail at arm’s length. As “information” on the retina moves away from the fovea, toward the periphery, there is a reduction in acuity (or an increase in spatial imprecision). So if an object is large, (covering a large angle), the eyes must constantly shift their gaze (saccade and fixate) to bring different aspects of the object into the fovea. Therefore, working at only intimate proximities to your painting or drawing may diminish your ability to productively explore important visual relationships with good acuity. An effective means to contend with this issue is to simply increase the distance from the artwork so that the area of focus yields a smaller visual angle, thus bringing more image properties together for comparison.

Furthermore, stepping away from a piece can allow us to spot unfortunate distortions that may have occurred from working in close proximity or other convenient orientations and provide us with the opportunity to reset some of the perceptual adaptations that might adversely influence some of our decisions after lengthy, static sittings.

However, like every aspect of an observational representationalist effort, “stepping back” is not without a pitfall or two.

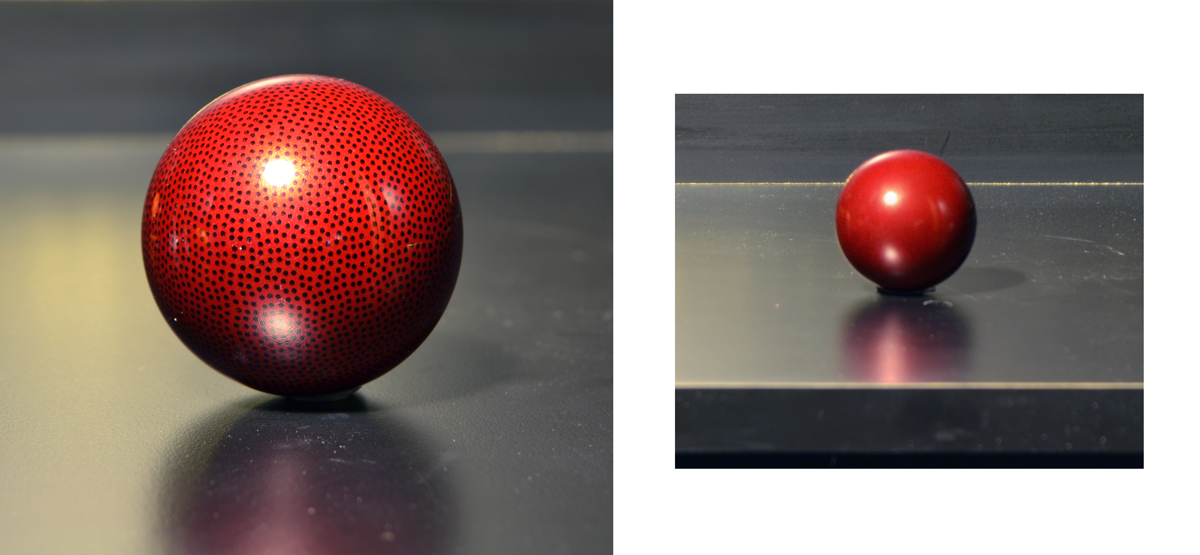

One issue that can create some uncertainty when an artist steps back from a painting/drawing and subject is the manner in which perceptually similar percepts elicited by different physical stimuli can seem to change, diminish, or even “average,” quite differently as viewing distances increase. Now many reading this might be quick to think, “C’mon, we aren’t moving THAT far back–how much difference can there really be?” Well, even though the standard observer is equipped with an impressively dense array of photoreceptors, the limit for our angular resolution is about 1/60th of a degree (or what is known as 1 minute or arc.) As such, it doesn’t take too much distance before we begin to experience disparities worth consideration. For example, here we can see a sphere that has its surface peppered with tiny dots. On the left, we see the sphere as it might appear to a standard observer at a viewing distance of about eight inches. On the right, we see the same sphere as it might appear to a standard observer at a viewing distance of about five feet. At the five feet mark, the pattern begins to fall under our angular or spatial resolution threshold, and we are left with a far more homogeneous looking surface.

For example, here we can see a sphere that has its surface peppered with tiny dots. On the left, we see the sphere as it might appear to a standard observer at a viewing distance of about eight inches. On the right, we see the same sphere as it might appear to a standard observer at a viewing distance of about five feet. At the five feet mark, the pattern begins to fall under our angular or spatial resolution threshold, and we are left with a far more homogeneous looking surface.

So how can this lead to a problem? I assume that as long as my painting surface and subject matter are oriented correctly, the perception of both subject (model) and surrogate (painting/drawing) should average in the same way, at the same rate, …right?

Not really.

Let’s take a look at an interesting experiment with a three-dimensional subject (nature) and a two-dimensional representation (surrogate). On the left is an image of two subjects (A). While they may look nearly identical, the one on the far left is, in fact, a photograph of a clementine (so yes, you are indeed currently looking at a photograph of a photograph) while the other is a photograph of the actual clementine (nature). (and yes, I do recognize that the results shared here are unfortunately limited by a photographic process, so I encourage you to try this experiment on your own with a photograph and actual subject.) Image (A) was photographed about 2 feet away from the subject while (C) is a photograph of the subjects taken from about 8 feet away. Image (B) is a smaller version of (A) for a more productive comparison with (C).

On the left is an image of two subjects (A). While they may look nearly identical, the one on the far left is, in fact, a photograph of a clementine (so yes, you are indeed currently looking at a photograph of a photograph) while the other is a photograph of the actual clementine (nature). (and yes, I do recognize that the results shared here are unfortunately limited by a photographic process, so I encourage you to try this experiment on your own with a photograph and actual subject.) Image (A) was photographed about 2 feet away from the subject while (C) is a photograph of the subjects taken from about 8 feet away. Image (B) is a smaller version of (A) for a more productive comparison with (C).

Just like with the sphere example presented earlier, you will notice that as the distance from the subject is increased—the smaller-scale, discernible visual information has been, generally speaking, averaged into a slightly more simplified percept. However, even though nature and the surrogate appeared nearly identical at more intimate proximities—the increased distance seemed to grow disparities between the two.

So why would this happen? One basic reason may be that while both subjects (A) do indeed yield a very similar percept in the context presented—the stimuli that elicit those similar perceptual responses are actually quite different in nature. This difference affects each percept differently as viewing variables (like distance) change. The representation on the left in image (A) was elicited from a flat plane coated with colorants that vary in reflectance properties while the representation on the right was elicited from both reflectance AND structural properties.

To this point, some emphatically argue that humans have an uncanny ability to avoid confusing proximal pattern variations originating from illuminated structural properties with those pattern variations originating from material properties like albedo or pigment. In fact, some have even proposed a number of interesting heuristics that our visual system may use for just this purpose (for more on this see Kingdom, Frederick AA. “Perceiving light versus material.” Vision research 48.20 (2008): 2090-2105.) I don’t know if such heuristics are indeed in play, but I feel confident in stating that changes in orientation, even along a single dimension as examined here, may produce disparities between percepts of nature and that of a surrogate that can be misleading in the context of an observational representational effort.

So if this snapshot of a clementine (A) was, in fact, a high-definition, observational representational effort that you were engaged in—and when you stepped back you noticed this disparity between the percepts of the subject and the painting–how would you proceed? Would you change the painting (represented by the photograph of a photograph here) to better match the observed value/color relationships found with more distant percept? Or would you opt for the relationships perceived within a closer proximity? I’m sure the answer would depend on many variables not introduced here—but it is my hope that considering the question may help you to appreciate that a representation (drawing/painting) can be considered accurate in one sense but still display noticeable disparities in another.

Regarding my own efforts, I contend with these issues by trying to find an ideal balance of visual information (relative to my goal of course) that communicates the subject effectively whether it is viewed from across a room, or from a few inches away. This often means the employ of a non-linear process that is shaped not by the misleading dogma of painting what I see or what I know “accurately”–but is shaped by a system of mark making that aims to communicate something as accurately as possible to a potential viewer. It may seem like a subtle difference in how I’m trying to be accurate, but this latter mindset allows me to explore the concept of accuracy in what I believe is a far more productive manner.

To this latter point, I would like to again remind my readers that the majority of my strategies for effective observational representationalist painting are shaped by the idea that visual perception is non-veridical. I operate under the assumptions that the perceptions generated by a biological vision system do not accurately portray the physical world. What we “see” is a construct of evolved biology—not an accurate measurement of an external reality. The mechanics of the visual system should not be confused with devices that can garner reasonably accurate/precise measurements of the physical world (e.g. calipers, light meter, spectrophotometer, etc.) Rather, the visual system reflexively responds to environmental stimuli based on past experiences and stored information in an effort to yield successful behavior. Some continue to argue against this idea to varying degrees, but very often those arguments are unfortunately built on with misrepresentation, misunderstanding, logical fallacy, and inexperience. In fact, the most recent counterargument I’ve encountered implied that vision may become more accurate/veridical when percept properties reduce in complexity. Unfortunately, this would be like me arguing that the accuracy of my “clairvoyance” ability increases among “pick-a-card” prediction tasks when the number of cards in play is reduced. With this reasoning, if we limit the pile to one card– I’d hit 100% accuracy.

In all seriousness though, in my experience, effective high-definition percept surrogacy is not a product of a “linear” process. It is not something that is shaped by veridical perception. There are many dynamic factors and filters along the way that require much consideration. Perhaps, in time, we may come to understand that some part of vision, and representation, is nothing like what I describe—and if I’m still around on the day that such evidence is brought to light I’ll be sure to change my tune quickly. In the meantime though, I do hope that these papers challenge some of your assumptions, thus providing you the opportunity to influence your perceptions and understandings of your own Representationalist endeavors. There is much to explore, and I look forward to many more years of exploring it all with you.

Happy Painting.

So, am I to understand that a person without this “system” knowledge which you purport to be using in your work, the person attempting to paint a realistic Clementine would be at a severe disadvantage. Is that correct?

Thank you Marlene~~It depends on how you choose to define the parameters of “realistic” and how the information provided relates to it. “Realistic” is (fortunately or unfortunately) a far more nebulous term than one might think (hence the quotations used at the first instance of the term in the article.) I do acknowledge that for some, a good bit of the information that I pass along might seem more esoteric than pragmatic—but such disparities and qualitative assignments are defined by your own methodologies. What you may find esoteric in this context, may be be of great practical advantage when you face the fact that convenient heuristics can often provide a relative weak foundation for adaptability. So while you are correct in that this information can provide significant advantage in many contexts relative to a “realistic” endeavor—there are others where absence is NOT disadvantageous.

Is this what art ateliers do…pass on a “system” for painting the classical method? If this is true, what is to be gained by learning it besides the ability to impress others with your magical powers? It would seem an intelligent artist would quickly tire of such nonsense and that it would quickly go out of fashion once others catch on to the tricks used. Do you think that I oversimplify the matter? And does the camera play a role in all of this? It certainly speeds things up! That is the biggest challenge in today’s art circles in my opinion. How does one put out enough high quality work that will give the artist a fair return on his efforts?

I apologize for perhaps not fully understanding what you mean here. The beginning of your assessment is unfortunately a non-sequitur (i.e., a classical system is only good for impressing others..) and then it gets difficult to follow (maybe the oversimplification you mention.) What might help me is if I understood your position/perspective better so that could better engage with your questions and conclusions. It might help for a better discourse if you are interested. In any case, I sincerely appreciate your time and feedback here Marlene.

From my perspective it’s important to remember that any image we create as artists is a surrogate for our experience of reality. No painting or photograph is the object it depicts. Both photographs and traditional media are simply means to communicate ideas about what we see and experience. Understanding how our biology works allows us as artists to create effective communication. This communication can go in thousands of directions. Each medium has strengths and weaknesses relative to how we communicate the information our biology generates. Photography and hyper realism are just two possibilities. In comparison, the painter has a greater latitude than the photographer in how they elect to present information in the their art. The painter can be far more selective. But regardless of our chosen medium, the bigger question comes back to what you are trying to communicate.

The information presented here is part of the grammar of our visual language. Don’t think of this as tricks. Think of it as sentence or paragraph structure. The audience reading a story or an article doesn’t pay any attention to the grammar unless it’s faulty. And knowing how grammar works doesn’t limit a writer’s ability to communicate. Nor does knowing how grammar works limit a writer’s ability to break grammatical rules in effective communication. Quite the opposite.

I don’t worry about ‘realism’ per se in my own work. As a visual development artist I want to help an audience suspend their disbelief and accept that a pig can fly. As a teacher I want my students to understand how the grammar and biology are effecting their communication goals regardless of their chosen medium or what they hope to capture and express.

<3